"Perhaps One Day it Shall be Pleasing to Recall"

Revisiting another passage in Vergil's Aeneid.

I recently took a job teaching Latin at a small classical school in the Midwest. We are a few weeks into the school year now, and I am loving it so far.

Although I have done some tutoring on and off over the years, this is my first time teaching in a normal classroom setting.

While preparing for the school year, I asked my parents if they still had a collection of articles, handouts, notebooks, etc. that I’d kept from high school and college. It was a smattering of random things I’d held onto over the years, some of which — I reckoned — might prove helpful for teaching Latin. I was worried the papers had gotten lost when my parents moved to a new house.

Thankfully, we were able to find the papers and notebooks in question. I sorted through it all recently, and was pleased to find (among other things) handwritten English translations for hundreds of lines of Vergil’s Aeneid, all dating back to my senior year of high school.

I also found a number of small handouts from high school Latin classes (not shown above). I’m not sure the concept of a “handout” is universally understood, so perhaps I can elaborate: when some topic happens to come up in class, the teacher will pass out 1-2 sheets of paper with an assortment of short readings related to the topic. Each paper usually features a few items clipped and photocopied to fit onto one sheet of paper. These items could include an excerpt of an article from a peer-reviewed journal, a silly comic strip clipped from a local newspaper, or anything in between.

Anyways, the rediscovery of all this material — some of it dating back as early as the fall of 2011 — got me thinking about doing some more blog posts about some of my favorite passages from Vergil’s Aeneid. (In an earlier post I translated another excerpt from the Aeneid.)

Book I of the Aeneid begins by outlining the backdrop and themes of the epic poem.1 It then describes Aeneas and the Trojans facing a terrible storm at sea. (The storm happened because of scheming by the goddess Juno.) Many are lost or dead, and a few remaining ships end up on the coast of North Africa, near Carthage.

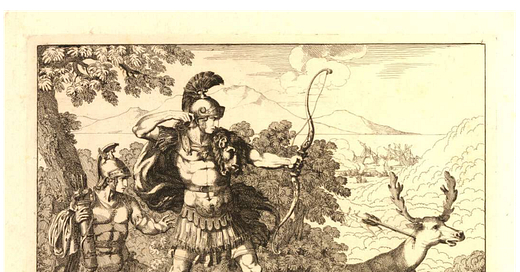

Once ashore, Aeneas climbs to the top of a peak to get a view of things, and kills some deer to provide meat for his people.

After the Trojans have a meal together (consuming provisions from the ships as well as the fresh game), Aeneas addresses the people and tries to provide some words of encouragement.

Here’s what Aeneas says to his fellow Trojans after their latest setback:

Oh companions — we of course are not unaware of misfortunes previously — oh you who’ve endured graver things! A god will give an end to these as well. You have approached the rage of Scylla, and the rocks roaring within, and you are experienced with Cyclopean rocks: restore your minds and send away gloomy dread; perhaps one day it shall be pleasing to recall even these things. Through various misfortunes, through so many dangers of events, we strive into Latium, where the fates promise quiet seats; it is divine will that Trojan kingdoms will rise there again. Endure, and preserve favorable things.”

O socii—neque enim ignari sumus ante malorum—

O passi graviora, dabit deus his quoque finem.

Vos et Scyllaeam rabiem penitusque sonantis

accestis scopulos, vos et Cyclopea saxa

experti: revocate animos, maestumque timorem

mittite: forsan et haec olim meminisse iuvabit.

Per varios casus, per tot discrimina rerum

tendimus in Latium; sedes ubi fata quietas

ostendunt; illic fas regna resurgere Troiae.

Durate, et vosmet rebus servate secundis.

(Bk. I, lines 198-207)

This is how Aeneas tries to encourage the fellow Trojans. He talks about their previous difficulties (alluding to things that will be explained to the reader in Book III, such as the “Cyclopean rocks”) as a way to show his people they have the strength to get through this.

There’s one particular phrase I’d like to unpack: “perhaps one day it shall be pleasing to recall even these things” (“forsan et haec olim meminisse iuvabit”).

When we endure hard times and misfortunes, it’s often quite excruciating in the moment. But, when we look back on it, sometimes we can look back fondly in some sense: perhaps proud of ourselves for how maturely we handled something, or perhaps remembering how the suffering brought us closer to our loved ones (to give two examples).

For us Catholics, perhaps this is also redolent of our concept of redemptive suffering: viz., that we can offer up our sufferings to God in a spirit of prayer and penance. In that sense, it might be pleasing, once the storm-clouds pass, to look back on the suffering and think about how such-and-such a pain or sorrow was changed into a kind of sacrifice pleasing to God.

At the same time, there is another, much darker way to interpret the phrase, “perhaps one day it shall be pleasing to recall even these things.” It’s possible Aeneas is expressing a deep-seated pessimism here, suggesting that, as bad as things are now, the future might be even more dreadful — to the point that present sorrows would seem pleasant by comparison. In other words, perhaps he’s expressing, in a subtle way, a fear that things could get even worse. But even if Aeneas (or rather, Vergil) is hinting at that second, darker meaning, it’s done in a subtle way, in the context of a speech meant to be encouraging amid hardships.

For myself, I think the first interpretation given above is probably the correct one, since it harmonizes with the rest of Aeneas’ speech. However, I’m open to the possibility that Vergil recognized the secondary, darker meaning of the phrase, and intended that as something of a subtle joke with readers — perhaps foreshadowing the warfare in the latter half of the epic?

It having more than one meaning at the same time is perfectly plausible, as Vergil’s poetry is replete with layers of meaning. As one scholar puts it:2

Like all genuine poetry, Vergil’s models, the epics of Homer, are essentially symbolic. Vergil, however, is far more consciously symbolic than is Homer. Vergil’s word imagery, with its transparent several deeper levels of reality, and his invention of images in which symbol becomes allegory are alien to Homer.

That’s all I’ve got for this post. I hope you’ve enjoyed it!

I should do a post someday about the opening lines of the Aeneid, as there’s a lot there to unpack.

From page one of The Art of Vergil: Image and Symbol in the Aeneid. Viktor Pöschl. Trans. Gerda Seligson 1962. University of Michigan Press—Ann Arbor.